Candy (1968 film)

| Candy | |

|---|---|

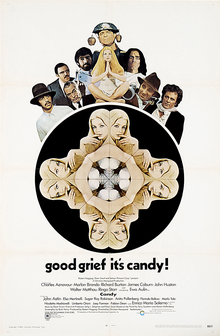

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Christian Marquand |

| Screenplay by | Buck Henry |

| Based on | Candy by Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg |

| Produced by | Robert Haggiag |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Giuseppe Rotunno |

| Edited by | Giancarlo Cappelli |

| Music by | Dave Grusin |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.7 million[1] |

| Box office | $16.4 million[2] |

Candy is a 1968 sex farce film directed by Christian Marquand from a screenplay by Buck Henry, based on the 1958 novel of the same name by Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg, itself based on Voltaire's 1759 novel Candide. The film satirizes pornographic stories through the adventures of its naive heroine, Candy, played by Ewa Aulin. It stars Charles Aznavour, Marlon Brando, Richard Burton, James Coburn, John Huston, Walter Matthau and Ringo Starr. Popular figures, such as Sugar Ray Robinson, Anita Pallenberg, Florinda Bolkan, Marilù Tolo, Nicoletta Machiavelli, Umberto Orsini and Enrico Maria Salerno also appear in cameo roles.

Plot

[edit]While in her father's social sciences class, high school student Candy Christian awakens from a daydream in which she seemingly descends to Earth from space. Following a poetry recital at Candy's school, eccentric Welsh poet MacPhisto offers her a ride home in his limousine. En route, MacPhisto forces himself on her but is unable to proceed after becoming too inebriated. With the help of her Mexican gardener Emmanuel, Candy takes MacPhisto inside to help him out of his liquor-soaked clothes. In the basement, MacPhisto drunkenly recites poetry while humping a mannequin, inciting Emmanuel to sexually assault Candy. Scandalized on walking in on the scene, Candy's uptight father decides to send her to live with his twin brother Jack and his wife Livia in New York City.

At the airport, the family is accosted by Emmanuel's three vengeful sisters, who accuse Candy of corrupting their brother. During the scuffle, Candy's father is rendered unconscious due to a head injury. The Christians escape by boarding a military plane commanded by General Smight. In exchange for a blood transfusion for her father, General Smight orders Candy to undress, intending to impregnate her. Meanwhile, he accidentally pushes the button that signals his paratroopers to leap from the plane. Realizing this, General Smight jumps as well, but slips out of his parachute harness.

After landing in New York, Dr. Krankheit meticulously performs surgery on Candy's father in front of an audience. When Uncle Jack attempts to seduce Candy during a post-operative cocktail party, the hospital's executive director, Dr. Dunlap, berates her for her perceived lewd behavior, causing her to faint. Dr. Krankheit takes Candy to another room and tricks her into sex by pretending to examine her. While searching for her father, Candy wanders back into the operating room to find that Dr. Krankeit has branded all the nurses with his initials as he prepares to do the same to Livia. When he attempts to have Candy captured so that she is next, she flees the hospital.

Roaming the streets of Manhattan, Candy ends up in a Sicilian bar in Greenwich Village, where she is beset by a group of mobsters. An offbeat underground filmmaker, Jonathan J. John, takes her into the men's room and records her for a film. As the room floods due to broken pipes, two policemen arrive and assault Jonathan, whereupon a drenched Candy escapes.

In Central Park, Candy meets a hunchback who takes her into a deserted mansion that night. A gang of thieves walk in and ransack the place, while the hunchback rapes Candy atop a grand piano. After arresting Candy, the two policemen maliciously plan to frisk her. However, they lose control of their squad car and crash into a club full of drag queens. As mayhem ensues, Candy escapes again.

The next morning, Candy hitches a ride in the back of a semi-trailer truck, which turns out to be the sanctum of Grindl, a sham guru. He teaches her the "seven stages of enlightenment" as a pretext to have sex with her. After several days on the road, Grindl informs Candy that a different guru will guide her through the rest of her journey. On arrival in California, Candy is chased through the desert by the New York police officers, but she manages to outwit them.

Shortly thereafter, Candy finds her new guru: a robed figure with a toucan on his shoulder, his face covered with white clay. She follows him into an underground Hindu temple, which partially collapses due to a cataclysm. As the two proceed to have sex, the guru's face is washed clean, and Candy is shocked to discover that he is actually her brain-damaged father.

As Candy wanders across a field—surrounded by flapping banners and hippies playing music—she revisits many of the characters whom she met throughout the film before finally returning to outer space.

Cast

[edit]- Ewa Aulin as Candy Christian

- Charles Aznavour as Hunchback Juggler

- Marlon Brando as Grindl

- Richard Burton as MacPhisto

- James Coburn as Dr. Abraham Krankheit

- John Huston as Dr. Calvin Dunlap

- Walter Matthau as Brigadier General Smight

- Ringo Starr as Emmanuel

- John Astin as T.M. Christian / Jack Christian

- Elsa Martinelli as Livia Christian

- Sugar Ray Robinson as Zero

- Anita Pallenberg as Nurse Bullock

- Lea Padovani as Silvia Fontegliulo

- Florinda Bolkan as Lolita

- Marilù Tolo as Conchita

- Nicoletta Machiavelli as Marquita

- Umberto Orsini as The Big Guy

- Enrico Maria Salerno as Jonathan J. John (G3)

- Joey Forman as the cop (Charlie)

- Fabian Dean as the sergeant

- Buck Henry as mental patient

Production

[edit]The novel was a best seller. According to Terry Southern, the original plan was for David Picker to produce and Frank Perry to direct with Hayley Mills to play Candy. However, Mills' father, John Mills refused to give permission. Then film rights came into the hands of actor Christian Macquand. Macquand managed to persuade his friend Marlon Brando to play a role (Marquant had recently helped Brando purchase an island in Tahiti). This attracted Richard Burton and other stars, which enabled Marquant to raise finance through ABC Films.[3]

Southern said Marquant "disappointed me by casting a Swedish girl [Ewa Aulin] for the lead role, which was uniquely American and midwestern. He thought this would make Candy's appeal more universal. That's when I withdrew from the film."[3] Marquand arranged for Buck Henry to write the script.

The stars were paid $50,000 a week with Burton, Brando, Starr and James Coburn getting a percentage of the profits. Coburn said, "That film could have been a lot more funny. Unfortunately, the director's timing was of a European nature. The jokes were always a beat behind. They were often a beat off. When you do comedy, you've got to be fast. I think [star] Ewa Aulin only did two films after Candy. Then she married an Italian count or baron. That was also the only film that I made any money on. I had a percentage of the profits. Marlon Brando and Richard Burton had the same deal. It's very unusual for an actor to see anything extra. Of course, that was before the studios set up their Chinese bookkeeping system (laughs)."[4]

Regarding the scene where Grindl attempts to seduce Candy, production manager Gray Frederickson said that Brando actually tried to have actual sex with Aulin on camera.[5]

Southern later observed, "The film version of Candy is proof positive of everything rotten you ever heard about major studio production. They are absolutely compelled to botch everything original to the extent that it is no longer even vaguely recognizable."[3]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Candy was one of many psychedelic films that emerged as the 1960s ended, along with others, such as Yellow Submarine, The Trip, Psych-Out and Head. The film opened to moderate box-office success, but later became a cult classic from the psychedelic years.

It was the 18th highest-grossing film of 1968. According to Variety, the film earned North American rentals of $7.3 million, but because of costs (including over $1 million paid out in participation fees), recorded an overall loss of $25,000.[1] It was the 12th most popular film at the UK box office in 1969.[6]

Critical response

[edit]Reviews were generally positive with a few misgivings. In a review representative of most professional reviewers at the time, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times found it "a lot better than you might expect", but missed the "anarchy, the abandon, of Terry Southern's novel".[7]

Renata Adler of The New York Times decried "its relentless, crawling, bloody lack of talent".[8]

John Simon of New York magazine wrote, "If you know someone you want to start the new year as nauseated as possible, send him to see Candy."[9]

Pauline Kael wrote that the film, "keeps getting worse than seems possible... a shambles of a sex spoof, and though it sticks fairly closely to the book, which was an erotic satire, it isn’t erotic."[10]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 40%, based on 10 reviews, with an average rating of 6.6/10.[11]

Accolades

[edit]In 1969, the film earned Aulin a nomination for New Star of the Year – Actress at the 26th Golden Globe Awards.[12]

Home media

[edit]Candy was released by Anchor Bay on April 10, 2001, as a region 1 widescreen DVD, and was released on Blu-ray by Kino Lorber on May 17, 2016, as a region A widescreen.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "ABC's 5 Years of Film Production Profits & Losses". Variety. May 31, 1973. p. 3. ISSN 0042-2738.

- ^ "Candy (1968)". The Numbers. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c McGilligan, Patrick (1997). "Terry Southern: Ultrahip". Backstory 3: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 60s. pp. 384–385.

- ^ Goldman, Lowell (Spring 1991). "James Coburn Seven and Seven Is". Psychotronic Video. No. 9. p. 23.

- ^ Hollywood Hellraisers: The Wild Lives and Fast Times of Marlon Brando, Dennis Hopper, Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson at Google Books

- ^ "The World's Top Twenty Films". Sunday Times. September 27, 1970 – via The Sunday Times Digital Archive.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 26, 1968). "Review: Candy (1968)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 10, 2020 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Adler, Renata (December 18, 1968). "Screen: 'Candy,' Compromises Galore; Film Faithful in Spirit to Satirical Novel". The New York Times. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ Simon, John (1971). Movies into Film: Film Criticism 1967–1970. New York: Delta. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-4405-5880-4.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (1970). Going steady. Temple Smith. p. 223.

- ^ "Candy (1968)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ "Ewa Aulin". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Candy at IMDb

- Candy at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Candy (The Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) at Discogs (list of releases)

- 1968 films

- 1968 comedy films

- 1960s American films

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s fantasy comedy films

- 1960s French films

- 1960s Italian films

- 1960s satirical films

- 1960s sex comedy films

- ABC Motion Pictures films

- American fantasy comedy films

- American satirical films

- American sex comedy films

- Works based on Candide

- English-language French films

- English-language Italian films

- Erotic fantasy films

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by Christian Marquand

- Films scored by Dave Grusin

- Films set in California

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in New York City

- Films shot in Rome

- Films with screenplays by Buck Henry

- French fantasy comedy films

- French sex comedy films

- Films about incest

- Italian fantasy comedy films

- Italian sex comedy films

- Teen sex comedy films

- English-language sex comedy films

- English-language fantasy comedy films